Greater love hath no man than this – that a man lay down his life for his friends (John 15:13)

Posted by SociusMar 17

“It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done;

it is a far, far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known.”

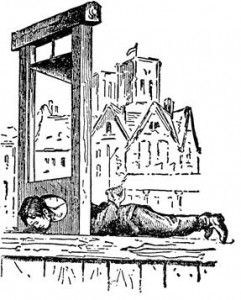

It is many, many years since I first read the words above, but I can still feel the lump in my throat as I came to the very dramatic ending of the ‘Tale of Two Cities’ by Charles Dickens. Also, as I remember, I found it exceedingly hard to hold back the tears, as Sydney Carton utters these, his final words, as he goes to the guillotine.

|

Now, some may put forward the view that the ending is over-dramatised, but, taken in context with the subject matter, the years of revolution and tumult in France, the propensities to war with England, and the social irregularities, inequalities and class struggles pertaining to both countries, towards the end of the 18th. century, all of this over-running into the 19th, I come to the conclusion that the ‘epitaph’ by which we remember Sydney Carton is entirely in keeping with themes and plot of the book. Having led a life, largely, of waste and excess, as the ‘tale’ progresses Sydney undergoes a change of character; at the finale, he enables a friend to escape the condemned cell, in the infamous prison Bastille, by taking his place, and this leads to his final journey on a tumbrel and a ‘date’ with ‘Madame Guillotine’.

Dickens, of course, was a story-teller par excellence, his perspicuity and sociological insights into the times in which he lived no less than legendary. However, he was, as I understand the man, much more than this, for many of his works are commentaries on morality. If one looks elsewhere among his books, e.g ‘David Copperfield’, ‘Oliver Twist’, ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’, ‘A Christmas Carol’, it is immediately apparent that all – plots, scenes and characters – depend for their ‘lives’ on human relationships – the ‘good the bad and the ugly’. Without those relationships, the moral lessons would not be driven home as they undoubtedly are.

The other not-so-surprising aspect of Dickens is his inherent Christianity. Yes, his work, in totality, relies heavily on the moral code – but this code is by no means a secular one. In many of his books there are echoes of the Church’s teaching running through them – delivering the same message at the end of the day as Jesus. Many of his main characters carry their crosses, day by day, and many pay the price in the yielding of their lives for the sake of others.

Greater love hath no man than this – that a man lay down his life for his friends (John 15:13)

Jesus came to us as a man, lived a largely ‘ordinary’ life at home with his ‘parents’, was subject to them, becoming apprenticed to St. Joseph to learn the carpenter’s trade. He would have ‘played’ with his friends in Nazareth, just as all lads do, but we know almost nothing of this. Thus he grew into a man and it was then that the ‘great call’ came, and he bowed to the will of His Father. He left home, parents and began his life of ministry, a life that was to end in the forfeiture of his life for his friends – for all those who accept him – accept his love – friends like you and me. And Jesus said, “…. you must take up your cross and follow me.” Obviously it is not given that all of us should become martyrs for our Faith, though down the centuries, there have been thousands, I suppose, who have done just that – followed Jesus, cross and all, right to the yielding of their lives in a holy death – a second baptism in blood. For the rest of us – the multitude of ordinary lives – lived as Jesus would want us to live, but without that fatal touch – it is still given to us to take up our crosses and to follow him. I think of the people I have known throughout the years of my life, and I am sure all of my readers, for example, can do the same, and whilst ‘scratching heads’ in a ‘blood-letting’ of memories, I cannot actually come up with even one that went through life ‘scot-free’ from problems along the way. It may be a truism to say that all life involves suffering of some sort – then, now, whenever…. …? The secret, I think, is to offer up those problems, those difficulties to God in some kind of reparation for sin – something we can do, but only because Jesus died for us and rescued us, in the first instance.

I made the point, above, that not all of us are given that singular grace, that enables us to give up our lives for God. But, from the many thousands who have managed to do just that, I mention, here, just two who gave their lives (in different ways) – for God, and for those people connected closely with their lives. In my last blog, 10 February 2011, I included two priests among those who have achieved sanctity in our lifetimes. The first of these, Father Maximilian Kolbe, was martyred in Auschwitz Concentration Camp, 1941, and the second, Father Damian, (Damien), who, whilst serving the lepers in the islands of Hawaii, contracted leprosy, himself, and died of the disease in 1889. The manner of these martyrs’ deaths was, factually, different, the first being executed, the second of a virulent disease – but, in essence, both gave their lives for their friends.

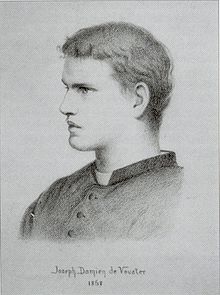

Father Damien of Hawaii: Born Jozef De Veuster, in 1840, the seventh child of a Flemish corn merchant, he entered the novitiate of the ‘Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary’, once old enough, and took the name, Damien, on the occasion of his first vows, thus following in the footsteps of his brother Auguste. As a missionary brother, he arrived in Hawaii in 1864 and,

|

Portrait of Father Damien, attributed to Edward Clifford, 1868, Honolulu Academy of Arts

shortly thereafter, was ordained priest, at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Peace, Honolulu. From there, he was assigned to the mission at North Kohala, on the Island of Hawaii. Round about that time, the islands were in crisis, many potentially fatal diseases having been introduced by foreign traders and sailors, and thousands died of influenza, syphilis and leprosy – to name just a few. Because of fears regarding the spread of leprosy, especially, those having contracted the disease were segregated from the rest of the island community, and over 8,000 were moved to leper colonies at Kalaupapa and Kalawao, divided from the rest of the island by a steep mountain range. This segregation was nothing less than a disaster for these easy going people, who became uncared for, neglected, and the easy-going and happy way of life became one of drunkenness and debauchery. The bishop, seeing what was happening wanted to send a priest to minister to the lepers’ needs, but realised that, in doing so, he was pronouncing a death sentence on any missionary chosen. After deliberations, four priests volunteered to go to the leper colonies, and Father Damien was the first of these to be sent to Kalaupapa, there to minister to 816 lepers. His first course of action was to build a church and establish the Parish of Saint Philomena, but his role was not limited to being a priest: he dressed ulcers, built homes and beds, built coffins and dug graves. Six months after his arrival at Kalawao he wrote to his brother, Pamphile, in Europe:

…I make myself a leper with the lepers to gain all to Jesus Christ.

Undoubtedly, his arrival in the colonies marked a turning point in the lives of the lepers; the people returned to their more civilized ways of life, basic laws were introduced, they had good housing, working farms to provide food, and schools the provide for their education.

In December 1884, while preparing to bathe, Damien inadvertently put his foot into scalding water, causing his skin to blister. He felt nothing, for, by then, he had contracted leprosy. He did not let this bother him, but worked vigorously at the programme he had designed for the continuing welfare of the lepers – a programme he hoped would be continued after his death. Now a leper, himself, Damien was well cared for by a Japanese Leprologist, Dr. Goto, and by his nurse, but, disease apart, he pushed forward his reforms for the community, giving and taking no respite. But the disease was taking no prisoners (as they say) and by March 1889 he was bed-ridden, the disease having by then taken hold of his limbs. He died in April of that year at the age of just 49. In 1995, Damien was beatified by Pope John Paul II and canonized, October 2009, by Pope Benedict XVI.

Father Maximilian Kolbe: Born Rajmund Kolbe, January 1894 in Zdunska Wola, which was part of the Russia, at the time, he was the second son of Julius Kolbe and Maria Dabrowska. He had four brothers, Francis, Joseph, Walenty (who lived a year) and Andrew (only to the age of four). In 1914, his father, Julius, was hanged by the Russians, for his part in the struggle for the independence of a partitioned Poland. His mother worked as a midwife – often giving her services for charity.

|

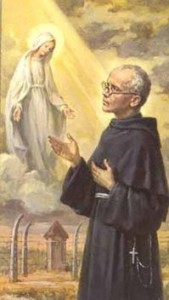

St. Maximilian Kolbe – Prayer Card

His life, even as a child, was strongly influenced by a vision of Our Lady:

“That night, I asked the Mother of God what was to become of me. Then she came to me holding two crowns, one white, the other red. She asked me if I was willing to accept either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity, and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both.”

In 1907, Rajmund and his elder brother, Francis, decided to become religious; they illegally crossed the border between Russia and Austria-Hungary and joined the Conventual Franciscan seminary in Lwow. In 1910, he was allowed to enter the novitiate and professed his first vows in 1911, whereupon he took the name Maximilian; he professed his final vows in 1914, in Rome, adding the name, Maria, as a mark of his devotion to Our Lady.

He completed his studies in Krakow and Rome, achieving a doctorate in philosophy, and it was during his time as a student in Rome that he witnessed violent demonstrations against Popes Pius X, and Benedict XV, largely orchestrated by young Freemasons. He describes the placing of a black standard, depicting the defeated archangel, St. Michael, lying at the feet of the Devil, and anti-Catholic pamphlets, as shameful attacks on the papacy. These events brought about Maximilian’s efforts to organize what he called the ‘Army of Mary’ to work for the conversion of sinners, and the enemies of the Church.

Maximilian was ordained priest in 1918, and shortly after that returned to Poland, now newly independent, where he was very active in promoting devotion to Our Lady – also in the founding of a monastery near Warsaw. In the 1930’s, he was engaged in a series of missions to Japan, founding a monastery on the outskirts of Nagasaki, and a seminary.

Back in Poland, in the early years of World War II, he provided shelter to Polish refugees including 2,000 Jews, whom he hid from Nazi persecution, in his friary at Niepolalanow. He was arrested by the Gestapo, early in 1941, and imprisoned for some three months before being transferred to Auschwitz Camp, in May. In July, three prisoners ‘escaped’ from the camp, and this caused the deputy camp commandant to pick ten men to be starved to death in an underground bunker, as a deterrence to further escape attempts. One of those selected cried out: “My wife! My children!” and it was then that Fr. Maximilian volunteered to take his place. In the starvation cell, he celebrated Mass each day for as long as he was able and gave Holy Communion to the prisoners, covertly, during the course of the day; the bread and wine for the Eucharist came from some of the kindly guards – sympathetic to the plight of the condemned men. He led his cell-mates in song and prayer, and encouraged them, telling them that they would soon be with Mary, in Heaven.

|

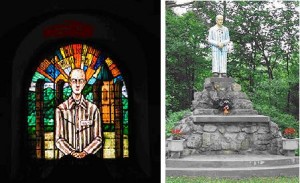

Stained glass of Maximilian, prisoner, Franciscan Church of Szombathely, Hungary, and Monument to Maximilian at Chrzanow, in Poland

When the cell was checked, he was usually standing, or kneeling, in the middle of the cell, his demeanour being one of calm throughout. After two weeks deprived of food and water, only Maximilian remained alive, and it was then, because the authorities wanted the bunker emptied that they gave him a lethal injection of carbolic acid. His remains were cremated on August 15, the feast of Our Blessed Lady’s Assumption.

Father Maximilian was beatified in 1971, and later canonized, as a martyr, by Pope John Paul II in 1982.

St. Damien, St. Maximilian and all holy martyrs, pray for us, that we may receive the grace from God, to renew and strengthen our faith. Amen.

Readers are advised to visit the main blogsite to see the article in its original formatting: www.stmarysblog.co.uk/

2 comments

Comment by Longchamp Le Pliage Autumn Winter 2014 on July 13, 2014 at 2:31 am

What a lovely blog. I will surely be back. Please maintain writing!

Comment by Socius on July 15, 2014 at 8:20 am

Thank you for your very kind comments -Socius