The Pharisees of Jesus’ days were those who kept the law, and were rightly known as the ‘pious’ Jews. It is probable that Joseph and Mary, Zechariah and Elizabeth, Simeon and the widow, Anna, and of course many other pious Jews would have been associated with this group. I have heard the comparison with today’s Catholics who come quite often to weekday Mass, many of them on a daily basis.

|

Picture of a man at prayer

They were good people, and Jesus, himself, may have been involved in that group. Certainly he was used to visiting the synagogue, in Nazareth, for Luke, the Evangelist, wrote that Jesus was accustomed to be in the synagogue each Sabbath (Lk 4: 16). In Matthew’s Gospel, there is a fascinating sentence that opens up a huge vision about the ‘heart’ of the teaching of Jesus, in the Gospel. It goes like this:

When the Pharisees heard that Jesus had silenced the Sadducees, they gathered together, and one of them, a lawyer, asked him a question to test him. ‘Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?’ He said to them, ‘“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.” This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: “You shall love your neighbour as yourself.” On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.’ (Mt. 22: 34-40)

|

The Pharisees and the Sadducees

The first little phrase does hint at the Pharisees being rather pleased that Jesus had silenced their rivals, the Sadducees. Interestingly enough, the Sadducees were like the upper classes in the Jewish Society, and Jesus, son of a carpenter / builder would be, in our terms, a working man. In England, the working man is mostly regarded as having a ‘provincial’ accent, whilst those of the English ‘nobility’ most often speak with an ‘upper-class’ accent that is hard to define; invariably, it is given the accolade of an ‘Oxford’ accent – an accent that is universally accepted as markedly different from those of the provincial accents, found throughout the length and breadth of island Britain.

I doubt if things were precisely like that in the Palestine of Jesus’ day, but the comparison may help us with an insight, into the kind of ‘class’ divisions that Jesus faced, in his own day. The fact remains that Jesus had silenced the Sadducees, who were chiefly among the priests of the temple in Jerusalem, in charge of administration of their country; they organised the collection of taxes, equipped the army and were responsible for official Jewish relationships with the Roman rulers and occupiers.

Those Sadducees must have been ‘galled’ that they had lost the argument with Jesus – a man from a much lower social level. At the same time, the ordinary people followed Jesus, a man, whom, they realised, was genuine and authentic, unlike these ‘leaders’ of the Jewish people. It is a sad fact that, even today, most ordinary people in our country are not too trusting of the leaders in politics, banking, sport, fashion, commerce – even, at times, in the Church – despite the high and noble calling it is to be a leader, in different spheres of the country’s life. When one comes to think about it, nothing much changes – there’s nothing much new under the sun!

Then the Pharisees ‘gathered together’ and I can imagine them in a little ‘huddle’, rejoicing in the discomfort of the Sadducees and so it became their turn to think out a question to ‘test’ Jesus. They were those who represented the pure Jewish religion: by comparison today’s parallel might be with those who regard themselves as ‘sticklers’ for what are the Church rules – rules that are never bent to accommodate the needs of the people, despite those needs becoming desperate at times. It could be the rather harsh ‘tut-tutting’ in Church, these days, when a harassed mother is trying to control her young child, who is making a noise, and the ‘good’ Christians are a bit ‘put-out’.

There is a wonderful example, given in the Gospel, of the lady who for eighteen years, had been bent double, virtually crippled. Jesus saw her and called her over to him; then, quite simply, he said to her: “Woman, you are set free from your ailment.”

|

The Lady Doubled-up in Pain

When he laid his hands on her, she stood up straight, immediately, and began praising God. Well, no wonder that lady gave praise to God, as eighteen years of misery was taken away from her by Jesus”

At this point, we are introduced to the leader of the synagogue, who would have been a Pharisee with a mission for ritual purity, and perfection in the ‘law’. He was angry with Jesus because Jesus he had cured on the Sabbath, and he spoke to the crowd that surrounded Jesus: “There are six days on which work ought to be done; come on those days and be cured and not on the Sabbath day”. Jesus’ reply, in perfect charity, went straight to the point: “You hypocrites! Does not each of you on the Sabbath untie his ox or his donkey from the manger, and lead it away to give it water? And ought not this woman, a daughter of Abraham, whom Satan bound for eighteen long years be set free from this bondage on the Sabbath day?” The crowds rejoiced at Jesus, and all his opponents were put to shame. (Luke 13, 10-17).

How much more wonderful, it is, when somebody has had something on their conscience for years, and years, often becoming a burden too heavy to bear, and then, at last, it is removed by God’s power, in the Sacrament of Reconciliation. That great joy has been mine to give out on various occasions. One man I knew, from Bamber Bridge, had been burdened for over 40 years, as I remember; soon after his release from his own sense of unworthiness, before God, he died and went to his eternal reward.

|

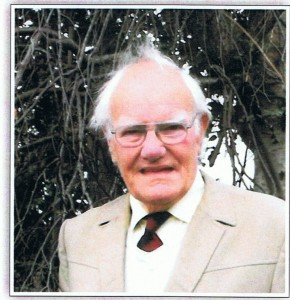

Man – in Freedom

The heart of the Gospel of Jesus is to love God totally, (in Latin, ‘totus tuus’ – completely yours), and your neighbour, as yourself. What all this implies would be the subject of another blog, but of one thing we can be certain – it is freedom from being ‘shackled’ by fear and scrupulosity, giving each man, and each woman, the chance to hold his, or her head, up high, in that sure and self-confident knowledge of utter dependence on God, and his love, in company with others who belong to the same family of God.

|

Woman – in Freedom

To put things in a ‘nutshell’, the heart of the Gospel is ‘LOVE’

In e-mailing the blog, ‘Word Press’ tends to distort the original formatting of the document. Readers may wish to visit the website www.stmarysblog.co.uk to read it in its original format.