People Who Leave a Lasting Impression:

Posted by Fr. JonathanOct 13

It is a rather strange phenomenon, that often, when a person dies, we see them in a ‘different light’ than when they were alive. I well remember a parishioner, who looked after her mother when her mother lived just across the road, from her. In her old age, the mother was very demanding, and three to four times each day, her daughter would cross the street to tend to her mother. It was a seemingly caring ‘chore’ until the old lady died. The daughter then felt ‘lost’, without her constant caring for her mother, a mother she valued so much more. Time passes, and we can then look, quite realistically, at our past experiences, but it remains true to say, that when a person dies, often we see them in a different light; in my experience, it is then a ‘better, warmer and often more appreciative light’, than when they were alive, though there is no ‘hard and fast’ rule to this.

|

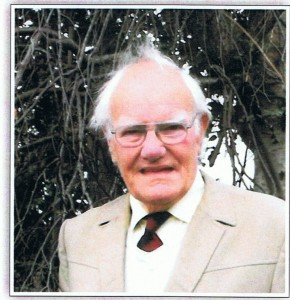

Martin Kevill

Very recently, I officiated at the funeral of a local man – not strictly speaking a parishioner – but one who often came to Church here. His name was Martin Kevill, who for years, lived at Bradwell Farm, Croston, where he became a successful business man. He was ever unconventional in his life-style; his attitude to things, his attitude to people, in his whole being, he refused to ‘conform’. Even in his clothes, he dressed without concern for looking ‘smart’, and although he came from the best of Lancashire’s ‘social circles’, he was most ‘at home’ with those who, we might say, were the lesser important people, in the eyes of the world. He would challenge all, from the top, to the bottom of society, by what he believed and what he talked about; in this, he was never afraid to let others know his own opinions, on important matters, e.g. faith, or moral issues. He wrote a short autobiography called, “The Haunted Man”, and its title provides an insight into the author, himself.

As a priest, one is privileged to preside at the funeral of a person, who has, so recently, left this world behind; in this, it is very helpful to get to know something about the deceased. In the planning, I was not meant to be the priest-in-charge at Martin’s funeral, as he had arranged the whole etiquette some years ago, with Fr. Ambrose. However, Fr. Ambrose died in June of this year – pre-deceasing Martin by about three months. I did get to know Martin, to some extent, personally, and had met various members of his family – nephews, his brother Roger Kevill, who lived in Bamber Bridge, when I was there as a curate. However, Martin’s health had, more latterly, deteriorated and the last period of his life was spent, very happily, with the Augustinian Sisters, at Boarbank Hall. In fact, his last trip from the Hall was when he attended the funeral of Fr. Ambrose, 30th June 2011, in our Church. Once that quite beautiful ceremony was ended, Martin asked me to preside at his funeral Mass; he then told me, what I already knew, as Fr. Ambrose, when dying, had also suggested that I should take care of Martin’s funeral. I will never forget the goodness and charity, embodied in his personal request to me, at the same time, placing in me his complete trust; I was also struck by his ‘matter-of-fact’ manner, and the frank way in which he talked about it. It was also on this occasion that I met with Tony Calderbank, a friend of Martin’s for 40 years, and with whom he had discussed, in detail, all these funeral arrangements, and with whom, I should be in touch when ‘anything happened’.

Before the funeral, I had the opportunity to meet with Martin’s niece, with Tony Calderbank and his wife, Margaret, from Chorley. By this time, I felt then I had got to ‘know’ Martin, much better than in the past, and after my fairly brief encounters with him. It was only after he had died that I began to realise why he had never married – a realisation that he was immensely shy. I also came to understood, on reading his very brief auto-biography, why he was such a ‘philanthropic man’, loving all those in need, especially the poor. At heart, he was deeply religious, having been ‘reared’ in a devout and well-to-do Lancashire family; from his childhood, his mother helped him to respect and understand the people of Lisieux Hall – those with ‘learning difficulties’ he’d encountered as a young boy; she taught him that each one of those people were brothers to be loved and cherished. This is how he put it:

“When I was younger, in the early 1930’s, we were taken for a walk every Sunday afternoon through the delightful village of Whittle-le-Woods, near Chorley, and into the Whittle hills. The walk always seemed to coincide with a large group, walking in ‘crocodile fashion’ from Lisieux Hall, the home for physically and mentally disabled men, run by the Brothers of Charity. I was only four and a half years old, but I used to ask my mother: “Why do they seem different to other people?”

|

She replied: “They are not as lucky as you are; they have been left with great difficulties of mind and body.” She went on to describe what a ‘straight-jacket’ was, before explaining that they lived in a ‘perpetual straight-jacket’ throughout the whole of their lives. My mother was strong on the point, that we must always be kind and generous to them, as they would always be dependent on other people to look after them – carers to help them throughout their lives. Without this help, she said, they would lead very unhappy and sad lives.

“She taught me never to be unkind to them, and always to help them, whenever possible. In the eyes of God, she said, they were, probably, much more highly thought of than we were. She told me never to laugh at them, as their ‘condition was through no fault of theirs, and, in any event she warned, one never knew, in life, what could happen, at any time. A sports injury, a car accident, brain damage, or a stroke, as one gets older, could leave a person finding out, late in life, what these residents from Lisieux Hall, have endured throughout the whole of their lives; it also may well leave one with the feeling that one might wish one had helped them whilst one were able.”

Martin learned to call this group ‘people with learning difficulties’, because, at that time, the name had more dignity attached to it. He also discovered that, in the world at large, there are about 250 million such people, and it was here that I discovered why he called himself, ‘a haunted man’; it was because the ‘sadness’ of some such people, together with ‘others in need’ haunted him all his life. I believe the root of this was because of his own ability to ‘identify’ with the ‘simple’ and ‘uncomplicated’ needs of such people. His own personal shyness, probably, assisted him in this, as did his clear belief in God, who taught us, through Jesus, that whatever we do to the least of our brothers, or sisters, we do to Jesus, himself.

|

However, Martin was, certainly, no conventional saint. In his unconventional ‘other’ direction, he loved a good and long drink; he loved to go into the pub and have a ‘skin-full’ and he loved’ generously’ helping people. He had his own self-discipline, however, never drinking on his own, but only in the company of others.

After his schooling, which took him to Ampleforth College, Martin joined the Welsh Guards, in 1944. He was in Northern Germany, after Peace was declared in 1945, and had some ‘strong’ experiences seeing mentally, and physically-handicapped children, saved by peace, from the ‘gas chambers’ of the Belsen Concentration Camp. Around the time, he also almost accidentally lost his life, in Gdansk, and, in regard to this, he wrote: “Many of us were thrown into the water when the quayside gave way and I was knocked on the back by a piece of concrete, which knocked me unconscious. Apparently, a Russian sailor fished me out and, presumably, saved my life. I would have loved to have met him”. When he arrived home, in Britain, the prognosis was paralysis of the legs, for life. One day he was feeling ‘very low’, and one of the gentlest monks of our Abbey, Fr. Gerard Sitwell, went to visit him in the Wheatly Hospital, Oxford – a hospital for head and spinal injuries. Martin ‘blurted out’ to Fr. Gerard: “Father I will try my vocation, as a Benedictine monk, if I regain the use of my legs”. He continues his story: “As luck would have it, there was a famous neuro-surgeon, Sir Hugh Cairns, a brilliant Scotsman, and he operated on me; it was a dangerous operation on my central-nervous system; after the operation, though ‘cast’ in a ‘plaster jacket’, I began to get the use back into my legs, and eventually, I made a substantial recovery”. Martin then entered Ampleforth Abbey, in 1948, and remained there for 14 months; his fellow novice, Fr. Nicholas Walford, remained his friend, and used to come and visit him, right to the end of his life. It was Abbot Herbert Byrne, who told Martin, after the recurrence of a nervous complaint, that ‘he had served his contract with God’, and who said to Martin: “You may leave the monastery. God bless!” That was in 1950.

|

Martin tried to share his ideas, and ideals, in imaginative ways. He built his own ‘millennium dome’ which had both the ‘Beatitudes’ and the ‘Ten Commandments’ displayed on it, as well as the contrast between the very rich, and the very poor, of the world. I remember, he showed me Bill Gates (of ‘Microsoft’ fame), who had a personal wealth, way in excess of the whole annual budget of many poor countries, in our world. He gave away his farm, and his money – almost a half-million pounds – then teaming up with the ‘Sons of Divine Providence’, to live in a caravan, at the back of his property, surrounded by a huge number of Garden Gnomes. He remained loyal to the British Legion, to the Welsh Guards, to his Benedictine background and to his love for his country. He had a very strong love of Our Lady, and I have memories of him coming to Mass, at 12.15, in St. Mary’s, Leyland – always late, and always with a huge rosary in his hands. Georgie, his niece, told me he was late, because he was so shy! Tony Calderbank said to me, he was quite liable to urge himself, and his friend, to go to Confession on a Saturday evening, at Brownedge Church, and then, afterwards, think it a good idea, to go for a ‘couple of pints’ in the local pub.

Everyone I spoke with, about Martin, while preparing his funeral service, had felt ‘touched’ by Martin’s goodness. He was buried on the feast of Our Lady of Walsingham – the ‘English Mary’ – so to speak, which was a sure sign, and blessing from heaven, as is also the fact that this blog, will appear on the 13th October – a special day for Our Lady of Fatima. In the papers left for his funeral, and amid all his goodness, there was a marvellous statement of his faith, despite a lingering sense of doubt. Regarding this last comment, one can ask how many great ‘believing’ people have also felt God to be a bit remote! It is worth quoting Martin in full, to end this short, and authentic, piece of writing.

-

How I envy those who know without doubt that there is somebody called ‘God’ who lives in Heaven and can make them feel secure.

-

From the earliest possible age, I was taught there was a friend for little children who would send me to hell if I did not behave.

-

Later I read the Bible went to Church and listened to the knowledgeable – and now as an old man I still read the Bible, go to Church and listen to the knowledgeable.

-

Sadly, I’m further from understanding any of it than when I was a child, when, I truly believed there was someone called God, who lived in Heaven and makes me a good person, Amen.

-

I shall go on trying to understand and maybe all will be revealed. But time is drawing short. My only hope is that if there is a God living up there in Heaven – He’ll understand that at least I tried.

-

PS. The recent Easter Journal 2006 – Sons of Divine Providence helps me greatly. Pope Benedict says, ‘immersed like everyone else in the dramatic complexity of historical events, Christians remain unshakeably certain that God is our Father and loves us, even when his SILENCE remains INCOMPREHENSIBLE.

|

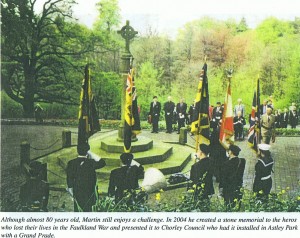

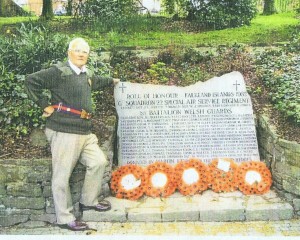

I never knew what devotion he might arouse in others, like the two middle-aged ‘bikers’ who came to his funeral, and who had been Welsh Guardsmen in the Falkland’s War. I never knew of his utter commitment to serving, and helping others, when he, himself, felt doubts as outlined above. But, I got to know, after his death, and, as I reflected on my own experiences, with him, and heard others, I realised that here was a man who truly loved his brothers, and sisters, with the kind of love God has for us, and who, consequently, got to know God himself.

As for me, I will side with Martin Kevill, as he sides with Pope Benedict.

To access the blog with its original formatting, you may wish to go to www.stmarysblog.co.uk/main/

No comments