Last Monday was my day off, and after a good night at my friends in Liverpool, I was off early enough in the morning and heading for Greenfield in Flintshire, North Wales, next to Holywell. It all turned out a lovely surprise for me.

|

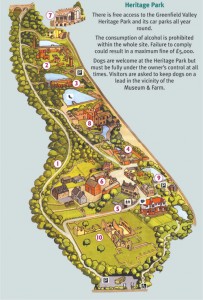

Aerial Map of the Greenfield Site

At the bottom of the aerial map, (No. 10) are the ruins of Basingwerk Abbey, founded some 750 years ago by the Cistercians and it was very good to go round and reflect on the monastic life led there, all those centuries ago by the monks of that era – that was until 1536, when the monastery was dissolved. The old abbey Church proved elusive for me, and in this diagram perhaps it is to be found at the very bottom of the picture.

|

First view of the ruins of Basingwerk Abbey

Eventually, after a walk up the beautiful Greenfield Valley, and having made a detour to enjoy open stretches of Welsh countryside, I hit upon the medieval shrine of St. Winefride’s Well (No. 7 in the aerial map).

St. Winefride was a beautiful young girl whose uncle, (the brother of her mother, Wenio), was St. Beuno. She had a suitor, Prince Caradog, and when she decided to become a nun and refused to marry him, he, in his rage, cut off her head; her severed head rolled down the hill, where it came to rest, and at that point, a spring of water with healing properties began to flow. The story reminds us of Lourdes and St. Bernadette, in some ways: in fact, the shrine is called the Welsh Lourdes. But, to return to Winefride, her uncle St. Beuno is said to have retrieved her head, whereupon he placed it back on her shoulders: miraculously she became alive again. Later, she did enter a convent, where she died in 660 AD.

A small ‘miracle’ happened to me on the occasion of my visit. The lady who looks after the shrine shop told me that, in an hour’s time, at 12 noon, there would be the daily service at the well, in honour of St. Winefride. Meanwhile, I looked round the museum and, as I did so, could not help but muse over the story of the well, St. Winefride, and the pilgrimages that had grown in number – particularly numerous under the Jesuits – who promoted the shrine in the early 20th century. It appears that there have been unbroken pilgrimages, from the death of the Saint in the 660 AD till today – thirteen hundred unbroken years of healing. As in Lourdes, there are the crutches on display from those whose limbs had been restored to health – all stored there. I did not linger to read, in full, the long story of St. Winefride, written in the 13th century by a monk scribe. For me, it seemed a little too ‘far fetched’. By 11.30am, I left the warmth of the museum, and still feeling ‘peckish’, went to see the medieval perpendicular shrine, built some time after 1500 to cover the well, by Margaret Beaufort, mother of King Henry VII and grandmother of King Henry VIII.

|

I sat down in the shrine, by the side of the water. It had been raining slightly as I had ascended the hill to this point; breakfast had been at 7.00 am, and I was not really in the mood to stay; rather, I would have preferred to get on with a good invigorating walk over the Welsh hills, and find some food. My mood was also coloured by my doubts about the ‘legend’ of St. Winefride, written in the 13th century, a long time after the supposed events. There were very few others about, and for 25 minutes I was left alone with my thoughts. It was then that I felt a change of heart:

“I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit in you; I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh.” (Ezek: 36, 26)

Mind in turmoil, I felt the need to do a wee bit of penance, to sit there and think of the mighty power of God; then I began to realise just how sceptical I had been, so many times in my life, preferring my own comfort to a short period of prayer in God’s presence. Furthermore, I did not like the ‘smack’ of superstition and sensationalism in the story of St. Winefride. However, I think this saint, in her own “pilgrimage place”, worked a small miracle in me. After all there had been centuries of pilgrims over the years going there, and they still do! It was my ‘inner attitude’ that was ‘worldly, negative and not open to faith’. I stayed the short time until a few minutes after 12 noon, a layman Minister of the Eucharist from the local parish, and myself, went through the litany of St Winrefride. I responded as he led me, supposing me, I think, to be an elderly lay-pilgrim come to say his prayers.

|

Relic of St Winefride

Saint Winefride; pray for us:

Glorious Virgin and Martyr: pray for us;

Fair flower of ancient Wales: pray for us:

That we may be delivered from disordered passions of the mind;

Virgin and Martyr pray for us…

In truth, I didn’t mind the ‘mechanical’ ritual; I didn’t mind the total lack of any relationship between us; I didn’t mind his unsmiling seriousness; I didn’t mind the cold, nor my empty stomach. When the ritual words had ended, the layman invited me to kiss the relic that he took from a felt covering. Was this really St. Winefride’s little finger? It made no difference to me, as I kissed it devoutly, and I drank from the well-water tap that is on the side of the building. It was a case of saying ‘thank you’ to my companion and departing. It’s true that for me Christianity could be expressed in a very different way. As I left, I felt much better, changed inside from my usual ‘hardness of heart’, that often prefers the easy path to self-satisfaction, rather than the harder, and humanly more difficult way, back to God. Penance and Prayer, even as small as this, is invaluable.

The experience made me realise that there is always hope; I need not be stuck in my usual negative thoughts on this kind of occasion. If I endure, God can show me his favour, and I can realise he has changed my heart into one of more compassion and love. The rest of the day was a delight – and, somehow, my spirit was uplifted.

Yes, there is always time to grow and change and develop and understand more about oneself and the mystery of God.

Fr. Jonathan